Ecuadorian Student Worldview Analysis

11-02-2023

One of the biggest determiners of ministry methodology is the underlying worldview of the target audience. This makes sense on the surface level; for example, using Bible verses to support your arguments is unlikely to convince someone who doesn’t believe the Bible is true. However, the importance of understanding the worldview of those around you goes beyond apologetics. Worldview is the lens through which people think about, understand, and make decisions about pretty much everything. Therefore understanding worldview is key to understanding others, and is an important part of building relationships.

I have just wrapped up two years of ministry to university students in Quito, Ecuador. As one of the world’s leading experts on the worldview of Ecuadorian college students1, I decided to write up a summary of some of my observations in the hope that this analysis will bless future ministry efforts2.

Methodology

To conduct the analysis, I made use of Cru’s Perspective Cards3, which describe a worldview by categorizing beliefs in each of five categories: Nature of God, Meaning & Purpose of Life, Nature of Mankind, Identity of Jesus, and Source of Spiritual Truth. Together, these provide ample insight into the core convictions of the person responding to the survey. In each category, the interviewee chooses the card that best represents his perspective; afterwards, the Christian worldview can be shared and key differences discussed. (I slightly modified the original cards by removing the “Truth is Relative” card from the sources of spiritual truth section, cleverly forcing the students to choose an actual basis for their beliefs.)

My findings include responses from 27 students4, curated from an original sample size of about 35. This represents about 45 hours of evangelism across 5 universities in 2 cities in the mountain region (meaning these results shouldn’t necessarily hold in other regions, where there are significant cultural differences).

Quantitative Analysis

For this section, I’ll analyze the breakdown in responses in each of the categories. Some of the options available in the cards are not present in the graphs because those responses were absent in my sample.

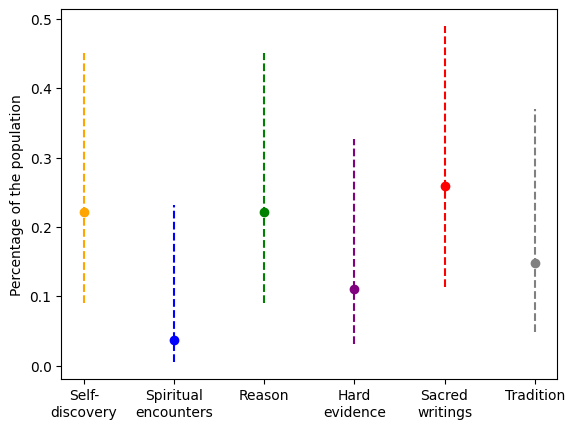

The dashed line in the graphs represents the 90% Goodman confidence interval5, whereas the point represents the proportion of responses present in my sample.

1. Nature of God

from statsmodels.stats.proportion import multinomial_proportions_confint

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

dios = np.array([10,2,14,1])

# 90% Goodman simultaneous confidence intervals for multinomial variables

ci_dios = multinomial_proportions_confint(dios, alpha=0.1, method='goodman')

sum_dios = np.sum(dios)

# create dataframe

data_dios = {

'category': ['Agnosticism','Atheism','Monotheism','Polytheism'],

'color': ['orange','blue','green','purple'],

'lower': ci_dios[:,0],

'upper': ci_dios[:,1]

}

df_dios = pd.DataFrame(data_dios)

# plot CIs

for lower, upper, y, color in zip(df_dios['lower'], df_dios['upper'], range(len(df_dios)), df_dios['color']):

plt.plot((y,y), (lower,upper), '--', color=color)

plt.plot(y, dios[y] / sum_dios, 'o', color=color)

plt.xticks(range(len(df_dios)), list(df_dios['category']))

plt.ylabel('Percentage of the population')

plt.savefig('dios.png', bbox_inches='tight')

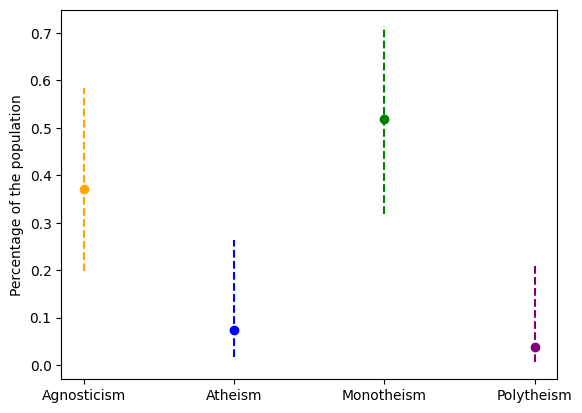

plt.show()The first category is “Nature of God.” In my sample, there were only two prevalent responses: monotheism and agnosticism. Around half of the sample was monotheist, suggesting that cultural Catholicism–for all its shortcomings–has at least succeeded in convincing Ecuadorians of God’s existence and nature. I recall that many of the people who responded as agnostics seemed to be weak agnostics (that is, instead of affirming that it is impossible to know whether or not God exists, they simply aren’t sure/haven’t investigated enough).

2. Meaning & Purpose of Life

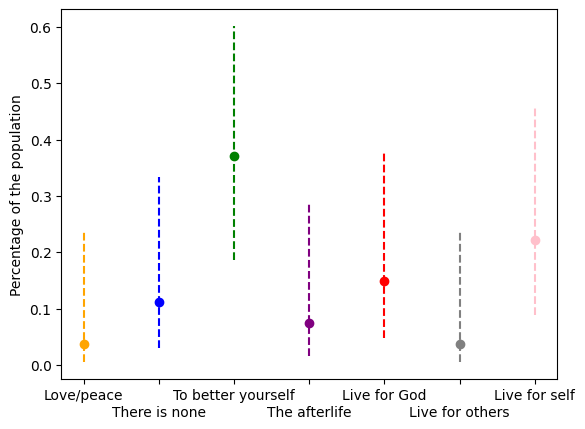

The next category is “Meaning & Purpose of Life.” Here, the responses were more varied, but there was a frontrunner at nearly 40%: bettering oneself, which likely coincides with university attendance. Of note, most people responded as if to say “this is my own purpose I’ve chosen for myself,” rather than to affirm an objective purpose for mankind as a whole.

3. Nature of Mankind

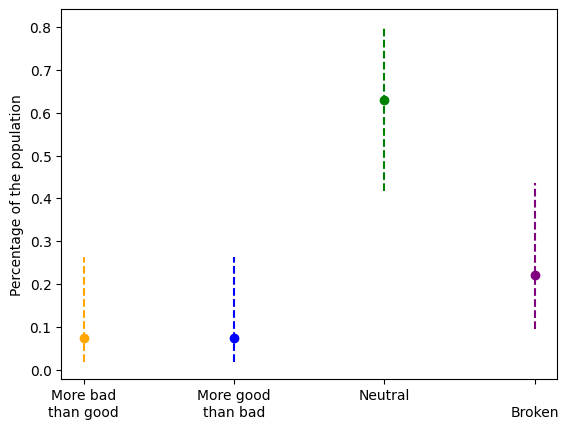

Next we have “Nature of Mankind.” Here Ecuadorian students are in overwhelming consensus, as over 60% of respondents chose “Neutral.” Of those who chose “Broken,” a decent portion meant it not in a Christian sense (as in, we have a corrupted nature because of the fall), but rather as a generic “This world is a pretty awful place.” This category seems like an obvious area to focus on, because understanding human nature is key to understanding the Gospel itself–more on that later.

4. Identity of Jesus

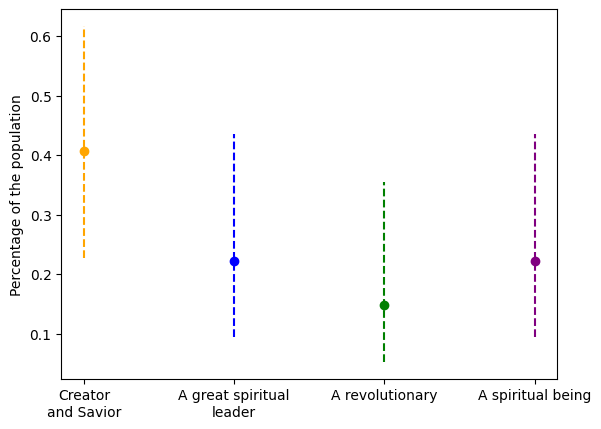

The fourth category is “Identity of Jesus.” Just north of 40% of respondents chose “Creator and Savior,” affirming Jesus’ divinity and his salvific mission. Unsurprisingly, the majority of respondents did not really exhibit much awareness of the implications of those beliefs when it came to the other categories, but cultural Catholicism has given us another inroad here.

5. Source of Spiritual Truth

In the final category, “Source of Spiritual Truth,” responses were more mixed than anywhere else. It seems telling that it’s precisely the source of one’s worldview where confusion was most prevalent; after all, without the correct source, the rest of the beliefs will inevitably end up pretty convoluted.

Qualitative Analysis

So, what do we do with all this information? I’d like to make a few cautious suggestions, based not only on the data but also anecdotally on my conversations and experiences in Ecuador.

First, when it comes to the nature of God: unlike in the US, Ecuadorian students often need no convincing of God’s existence or nature. This is a “freebie” for being in a culturally Catholic place; many people already share this aspect of the Christian worldview. Obviously, in an interaction with someone who’s not convinced of God’s existence, the conversation should focus on that; however, often you’ll be able to bypass this and go straight to other topics.

Second, on the meaning of life: I don’t think it’s usually worth spending a lot of time on this category, as the others are more likely to be the obstacle preventing someone from believing the Gospel, but it does remind me of something essential. Many students, in Ecuador just as around the rest of the world, have no objective purpose in their life and are just going through the motions. When we share the Gospel, we’re offering hope to people who have none.

Third, I believe that a misunderstanding of human nature is the most fundamental error in the belief system of Ecuadorian students. Often, when I shared the cards with the students, I asked them to choose both a) the card that best represented humanity as a whole (the data in the chart above) and b) the card that represented their view of themselves. When it came to their view of themselves, students were nearly unanimous in choosing “More good than evil.” Just like most fallen beings, Ecuadorian students were unable to recognize their own brokenness.

For the heart of this people has become dull,

With their ears they scarcely hear,

And they have closed their eyes,

Otherwise they might see with their eyes,

Hear with their ears,

Understand with their heart, and return,

And I would heal them.

I believe the root of most misunderstanding of the Gospel is based in misunderstanding our own need for redemption. If you think you’re a “good person,” you’ll also think that God will take it easy on you, that he’ll understand that we all make mistakes sometimes, and that there are a lot of people out there that are worse than you are. As evidenced by the data, if we don’t address this falsehood, we fail to share the Gospel.

I also believe this misunderstanding has serious implications for the way we share the Gospel. I’m generally not a fan of the Four Spiritual Laws/Knowing God Personally tract used by Cru6 (though I absolutely believe God has used it for His glory), as it seemingly glosses over the problems of sin and human nature without once mentioning hell or eternal punishment. After doing this study, I’m even more convinced than before that it is imprudent to use the Four Spiritual Laws as written when evangelizing this demographic. If the biggest obstacle to the Gospel is self-righteousness, we should confront that obstacle, not skim over it.

So what’s the best way to share the Gospel to Ecuadorian students? I can’t give a definitive answer here, but I’ve had limited success using the ten-commandments-based Living Waters method. I also think that the Four Spiritual Laws method can be modified in a way that makes it more effective; simply expound upon the second law by explaining what it means that the other person is a sinner, and add that they are under the wrath of God, in danger of eternal punishment. You’ll probably also want to clarify the first law by explaining that “wonderful plan” does not, in fact, mean what most people think of when they hear “wonderful plan”; this way, we avoid confusing people with some species of prosperity doctrine.

Moving on to the identity of Jesus: This is another area where, thanks to cultural Catholicism, you may not have to do much work. A bit north of 40% of the sample population affirmed a belief in Jesus as the “Creator and Savior”: Creator implying his deity, and Savior implying that his work on the cross purchased our salvation. Interestingly, very few of those who affirmed Jesus as Creator and Savior also affirmed him as Lord; that is to say, few of them appeared to follow Jesus’ teachings or be part of a local church, so it seems that the implications of Jesus being Creator and Savior were unclear to many. Here, the emphasis in evangelism may not be showing that Jesus is who he claimed to be, but rather prompting people who affirm his deity to think through the consequences of that for their lives and spurring them to action and repentance.

The final category, Source of Spiritual Truth, is perhaps the most telling one. The response data is all over the place, with no clear frontrunner(s). Probably the only safe conclusion is that the population doesn’t really look to Spiritual Encounters as the source of spiritual truth. However, there are some important conclusions to be made about the inconclusiveness: people don’t really know why they believe what they believe. In today’s culture of relativism, most Ecuadorian students appear to have bought into the buffet-style worldview: help yourself to a serving of whatever perspectives you like, and reject what you don’t. The result is a house of cards, an amalgam of contradictory beliefs that would crumble under analysis but manages to stand since it’s never really been analyzed at depth.

Conclusion

Tying these threads together, there’s one last point I’d like to emphasize: Most students don’t have significant intellectual barriers to receiving the Gospel. I rarely heard students defending their beliefs with much intensity or pushing back mine with any gusto. The truth is, most students don’t base their worldview on argumentation or logic at all. They typically don’t understand the gravity of Jesus’ claims or their sin against an omnipotent Creator, so explaining these concepts is all well and good; but at the end of the day, most students are unlikely to be convinced by such argumentation, given that they never placed much weight on arguments in the first place. Knowing a student’s worldview is likely more useful as a means to better understand him than as a way to show him his error.

There’s no magic formula to evangelize Ecuadorian students. Just as anywhere else, Ecuador needs Christian laborers who boldly proclaim the Gospel and love others daily, providing a consistent Christian witness. However, just like any demographic, Ecuadorian students have unique beliefs based on their cultural context. Christians who wish to be faithful to the Great Commission do well to note the unique perspectives of the people around them in order to preach the Gospel with clarity. It is my hope and prayer that, by God’s sovereignty, this analysis will enable others to do just that.

Soli Deo gloria!

1 [missing source]

2 The truth is, I’m really just doing this because I’m a stats nerd, but this gives me a good cover-up.

3 People familiar with the English translation of the Perspective Cards may notice that some of the categories have different names; this is because I wanted the categories to be as true as possible to the way that I explained them in Spanish.

4 True stats nerds will likely want to strangle me for coming to conclusions with such a small sample size.

5 Goodman, L. A. (1965). On simultaneous confidence intervals for multinomial proportions. Technometrics, 7(2), 247-254.

6 For a more in-depth treatment of these concerns, see God Has a Wonderful Plan for Your Life by Ray Comfort.